Google’s corporate headquarters in Mountain View, northern California. Source: supplied

The great enforced global experiment in working from home is coming to an end, as vaccines, the Omicron variant and new therapeutic drugs bring the COVID-19 crisis under control.

But a voluntary experiment has begun, as organisations navigate the new landscape of hybrid work, combining the best elements of remote work with time in the office.

Yes, there is some push for a “return to normal” and getting workers back into offices. But ideas such as food vouchers and parking discounts are mostly being proposed by city councils and CBD businesses keen to get their old customers back.

A wide range of surveys over the past 18 months show most employees and increasingly employers have no desire to return to commuting five days a week.

The seismic shift in employer attitudes is signalled by Google, long a fierce opponent of working from home.

Last week the company told employees they must return to the office from early April — but only for three days a week.

That’s still way more than tech companies such as Australia’s Atlassian, which expects workers to come into the office just four days a year, but it is a far cry from its pre-pandemic resistance to remote work.

Hybrid work is here to stay. Employers will either embrace the change or find themselves being left behind.

Gains in productivity

Google began — under pressure — to soften its opposition to remote work in 2020. In December of that year chief executive Sundar Pichai told employees:

“We are testing a hypothesis that a flexible work model will lead to greater productivity, collaboration, and wellbeing.”

Its chief concern has been protecting the social capital that springs from physical proximity — and also perhaps with keeping employers under surveillance.

But longstanding (and widespread) management concerns that employees working from home would lower productivity have proven unfounded.

Even before the pandemic there was good research showing no productivity penalty from remote working — the opposite, in fact.

For example, a 2014 randomised trial involving about 250 Shanghai call centre workers found working from home associated with 13% more productivity. This comprised a 9% gain from working more minutes per shift — due perhaps to fewer interruptions — and a 4% gain from making more calls per minute — attributed to a quieter, more comfortable working environment.

Research in the past two years supports these findings.

Harvard Business School Professor Raj Choudury and colleagues published research in October 2020 that found allowing employees to work wherever they like led to a 4.4% increase in output.

In April 2021, Stanford University economist Nick Bloom and colleagues calculated the shift to remote working resulted in a 5% productivity boost. Though their working paper, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, was not peer reviewed, it was based on surveying 30,000 American workers, which is a decent sample size.

Our relationship with work has changed

There are good reasons most of us don’t want to go back to the old normal. It just wasn’t that great.

While working from home can brings challenges of other kinds, not least the ability to switch off and stop working when work is done, working in an office can increase stress, lower mood and reduce productivity.

My own research has measured the effects of typical open-plan office noises, finding a 25% increase in negative mood even after a short exposure time.

Then there’s the time spent commuting. Not having to go into the office every day frees up hours of time to do other things. Particularly in winter it’s nice to not have to leave and arrive home in the dark.

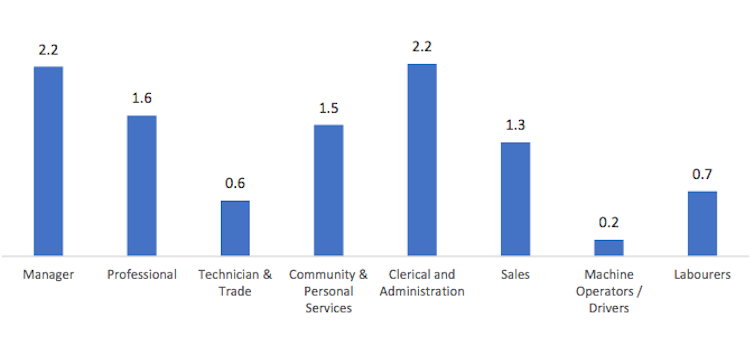

Preferred number of days working at home, by occupation

Institute of Transport and Logistic Studies, University of Sydney, CC BY

Changed expectations of work

The importance of these things should not be underestimated.

In a June 2021 study by McKinsey of 245 employees who had returned to the office, one-third said they felt their mental health had been harmed.

The experience of the pandemic has lowered our tolerance for this old world of work.

Nothing exemplifies this better than the growth of the “lie-flat” trend, which began in China and is now a global phenomenon. Increasing numbers of people are rejecting the idea of pursuing a career at all costs.

They don’t want to spend their life being a cog in the wheel of capitalism and are choosing to work less — even not at all.

No one size fits all

Rather than a bastion of meaning and fulfilment, the structures around how we have conducted work has for many people meant an existence of quiet desperation. The pandemic has brought an unforeseen opportunity to change this narrative and rethink both the way we work and the role of work in our lives

For some, no job is better than a bad job. The rest of us will settle for the flexibility we’ve had over the past two years.

No one size fits all. The downsides of working from home include missing coworkers and losing the benefits of serendipitous conversations. The nuances of how much time we need to spend together in the office for outcomes like creativity, belonging, learning and relationship building varies between individuals, teams and job types.

But what is certain is we don’t need to be together five days a week to make these things happen. With a shrinking workforce and an increasing war for talent, employers who don’t provide flexibility will be the losers.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Handpicked for you

Remote, overseas workers: What are the HR implications for employers?

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.