The Reserve Bank’s long-awaited two-year forecasts for jobs, wages and growth are frightening, but I fear they are not frightening enough.

The bank looks two years ahead every three months. The last set of forecasts, released at the start of February, mentioned coronavirus mainly as a source of “uncertainty”.

That’s how much things have changed.

Back then economic growth was going to climb over time, consumers were going to start opening their wallets again (household spending had been incredibly weak) and unemployment was going to plunge below 5%.

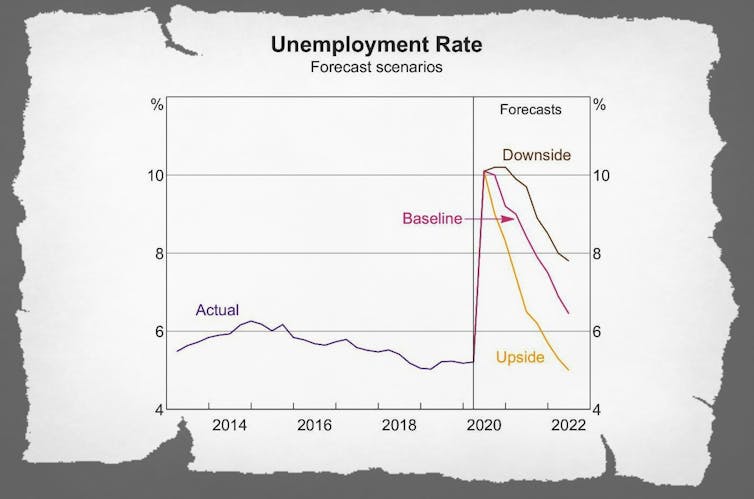

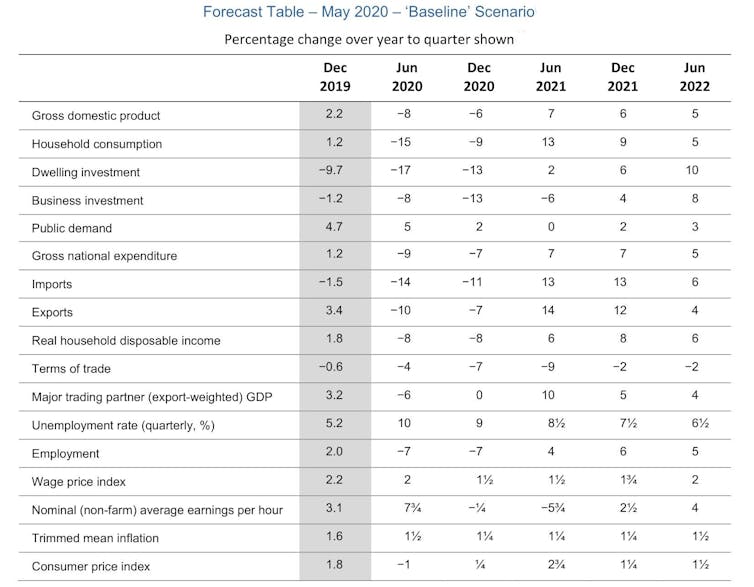

The forecasts released on Friday come in three sets — “baseline”, an earlier economic recovery, and a later recovery.

“Baseline”, the central set with which we will concern ourselves here, is both shocking, and disconcertingly encouraging.

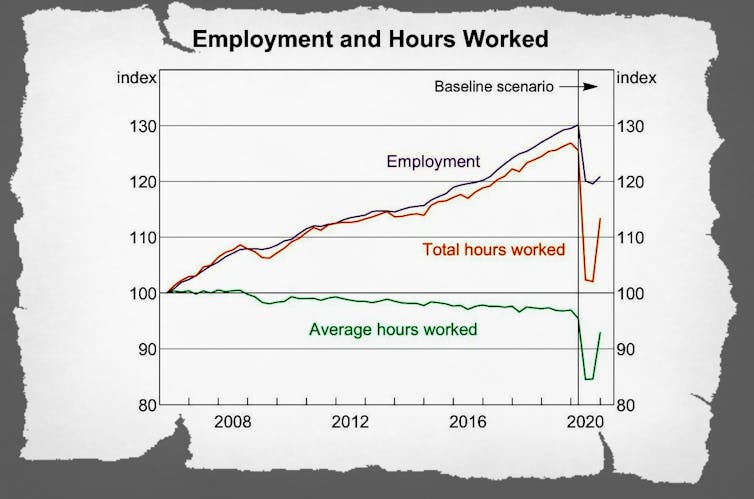

On employment, it predicts a drop of more than 7% in the first half of this year, most of it in the “June quarter”, the three months of April, May and June that we are in the middle of.

Thirteen million of us were employed in March, making a drop of 7%, a drop of 900,000. Put differently, one in every 13 of us will lose their jobs.

Harder to believe is that by December next year 6% of the workforce will have got them back.

It sounds like what the prime minister referred to earlier in the crisis as a “snapback”, the economy snapping back to where it was.

Except that it’s not.

Six per cent of a small number is a lot less than 7% of a big number.

The bank’s forecasts have far fewer people in work all the way out to mid-2022 (the limit of the published forecasts) and doubtless well beyond.

The unemployment rate would shoot up to 10% by June and take a long while to fall.

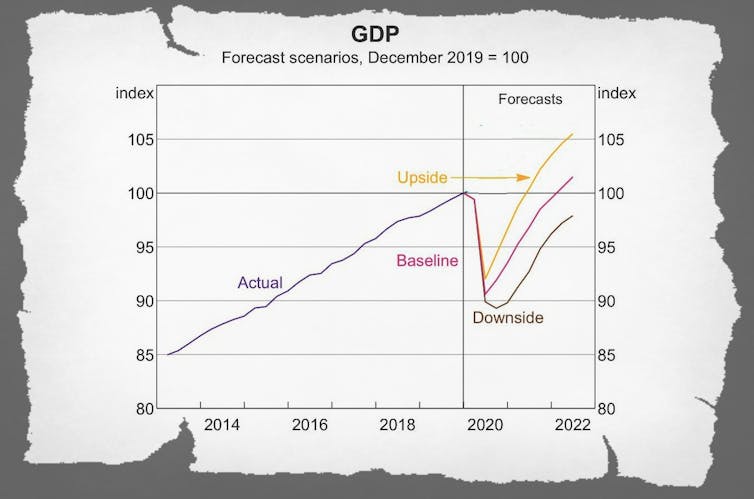

The baseline economic growth forecast is also drawn as a V.

After economic activity shrinks more than 8% in the June quarter, we are asked to believe it will bound back 7% in the year that follows.

But that will still leave us with much lower living standards than we would have had, missing the usual 2-3% per year increase.

The reason I fear the baseline forecasts aren’t frightening enough is that they are partly built on a return to form for household spending, which accounts for 65% of gross domestic product.

After diving 15% mainly in this quarter we are asked to believe it will climb back 13% in the year that follows.

Maybe. But here’s another theory. While we’ve been restricted in movement or without jobs we’ve become used to spending less (and used to flying less, and used to hanging onto our cars for longer and hanging on to the money we’ve got).

My suspicion is that these behaviours can be learnt, and we’ve been doing them long enough to learn them.

During the global financial crisis, we tightened our belts and then kept them tight for years, saving far more than the offical forecasts expected, in part because we had been shocked and felt certain about the future.

A recovery that had been forecast to be V-shaped looked more like a flat-bottomed boat when graphed. It’s a picture I find more believable than a snapback.

We are unlikely to get back where we would have been for a very long time.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NOW READ: Is slowing Australia’s population growth really the best way out of this crisis?

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.