Prime Minister Scott Morrison. Source: AAP/Mick Tsikas.

In this recession, unlike in previous ones, governments have chosen to help pay salaries to keep workers in work rather than pay unemployment benefits when they laid off.

It means that the July unemployment rate revealed on Thursday was 7.5% instead of the 8.3% it would have been had those working zero hours but being paid by JobKeeper been counted as out of work.

This approach has kept employees and firms ready for work at a time when it is far from clear when things will improve.

Implicit in the deal was that firms in need of JobKeeper would behave as if they were in times of immense uncertainty and not pay big dividends to shareholders on the assumption that things were rosy.

It is early in the company reporting season, but already there are signs that millions of dollars in increased dividends are being paid out by companies that received millions of dollars of JobKeeper.

As The Guardian’s Ben Butler puts it: “What we are seeing is a transfer of millions of dollars from taxpayers — the community at large — to shareholders, some of whom are already quite rich.”

By supporting the wages of employees in companies at risk, the government freed up money the companies could use to pay shareholders increased dividends rather than fortify themselves against that risk.

It enabled them to shovel out of the door the money the government was shovelling in, leaving themselves no better prepared than before.

And they need to be prepared.

The last thing we need is big dividends

In April, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority wrote to banks and insurers asking them to “seriously consider deferring decisions on the appropriate level of dividends until the outlook is clearer”.

Even where they were confident they had the resources they needed, their dividends should be at a “materially reduced level”.

Perhaps precipitously, it relaxed the guidance on July 29, noting that uncertainty had “reduced somewhat”.

A few days later, Melbourne went into stage four lockdown.

Its new guideline was for banks to retain at least half of their earnings when making decisions on dividends — an instruction the Commonwealth Bank followed to the letter on Wednesday, paying out 49.95% of its earnings as dividends.

That night on ABC’s The Business, the bank’s chief executive Matt Comyn conceded the outlook was “highly uncertain”.

Earlier that day, we learnt that the private sector wage index had stopped for the first time in its 27-year history.

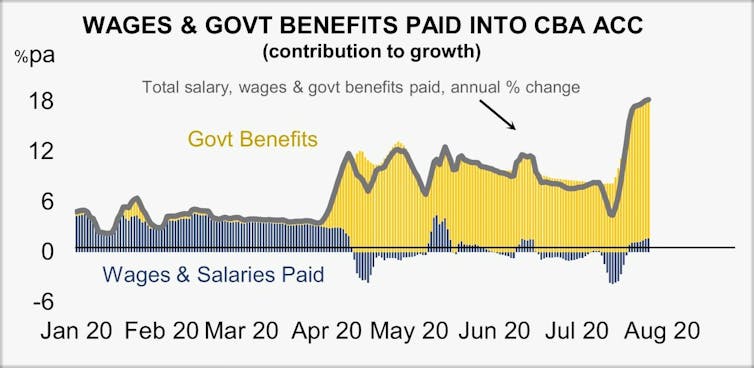

A graph presented to Commonwealth Bank shareholders on Wednesday shows that almost all of the increase in deposits in its accounts comes from government benefits rather than wages and salaries.

Commonwealth Bank results presentation.

Some 10% of all bank loan books are now made up of loans on which borrowers have been granted deferred payments.

Among small businesses, 17% of repayments have been deferred, a proportion set to climb from September as Job keeper subsidies are reduced and withdrawn.

In March the government gave companies temporary relief from rules that prevent them from trading while insolvent.

For the moment, the change has pushed insolvencies down to an all-time low, creating an unknown amount of zombie companies not fully alive but not yet dead.

When the temporary relief expires (in September, unless it is extended) there’s talk of a tidal wave of insolvencies.

It raises concerns that for now, many companies are announcing dividends that shouldn’t and ordinarily wouldn’t be paid.

And some (not the Commonwealth Bank), are using JobKeeper to pay them.

Why dividends, now of all times?

There is a relationship between dividends, share prices and executive pay. Australian companies that pay out big dividends keep their share prices high.

Many Australians receiving dividend imputation cheques, including many retirees, hold shares because of them.

Without them, share prices would fall and executives would be denied their bonuses.

One way to ensure that there is money available for dividends is to rule out new investments that can’t achieve a high rate of return, meaning money can be paid out to shareholders instead.

Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe has complained that hurdle rates of 13% to 14% seem to be “hard-wired into the corporate culture in some companies” notwithstanding the record low rates at which they can obtain funds.

In January, head of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Rod Sims warned that unless companies lowered their hurdle rates they would “risk missing investment opportunities to foreign raiders”.

It’s something akin to an undeclared investment strike by corporate Australia, something akin to “heads, shareholders win; tails, employee, creditors and the rest of us lose”.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.