Source: unsplash/Dominik Lange

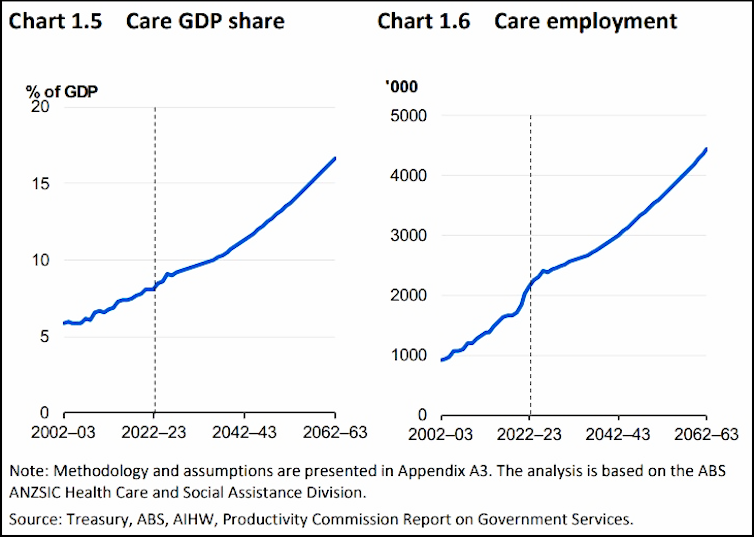

Australia’s care economy could increase from its present about 8% of GDP to about 15% in 40 years, according to the government’s Intergenerational Report, to be released by Treasurer Jim Chalmers on Thursday.

The projections say in four decades’ time Australians will be living longer, with more years in good health — but the larger cohort of aged people will increase the need for care.

By 2062-63, life expectancy for men is projected to be 87 years (currently 81.3), and for women 89.5 (85.2).

Australia’s population is expected to grow at a slower rate in the coming four decades than in any 40-year period since federation, according to the report, prepared by the federal treasury. By 2062-63 Australia would have a population of 40.5 million.

The Intergenerational Report puts a long lens on the nation’s future, looking at the implications of demographic changes and covering a broad range of economic and social areas. The first report was done under the Howard government and the most recent was in 2021. While these reports are important for policymakers in identifying trends and signposting looming problems, they are also limited by the extended time frame and the inevitability of changing circumstances and different policies.

This year’s report again highlights the economic and budgetary issues presented by an ageing population. The combination of increased longevity and low fertility means Australia will continue to age over the next four decades. “The number of people aged 65 and over will more than double and the number aged 85 and over will more than triple,” the report says. This will make for “an ongoing economic and fiscal challenge”.

“The average annual population growth rate is projected to slow to 1.1% over the next 40 years, compared to 1.4% for the past 40 years,” the report says. “Australia’s population is projected to reach 40.5 million in 2062–63.”

Present projections are for the number of healthcare and social assistance workers to increase by 15.8% from 2021 to 2026. The former National Skills Commission projected the demand for aged care workers alone was expected to double by 2050.

Chalmers said the report showed growth in the care economy “is set to be one of the most prominent shifts in our society” over the period, with the care sectors playing a bigger role in driving growth.

“Whether it’s health care, aged care, disabilities or early childhood education – we’ll need more well-trained workers to meet the growing demand for quality care over the next 40 years. The care sector is where the lion’s share of opportunities in our economy will be created,” he said.

The report projects population growth to fall to 0.8% in 2062–63.

Both migration and natural increase are expected to fall relative to the size of the population. Net migration is assumed at 235,000 a year.

“The 2023–24 Budget forecast that net overseas migration will recover in the near term due to the temporary catch‑up from the pandemic. It is expected to largely return to normal patterns from 2024-25. Even with the near‑term recovery, on current forecasts, cumulative net overseas migration would not catch up to pre‑pandemic levels until 2029-30,” the report says.

“Over the next 40 years, net overseas migration is expected to account for 0.7 percentage points of Australia’s average annual population growth, falling from 1.0 percentage points in 2024–25 to 0.6 percentage points by 2062–63.”

On budgetary pressures, the report follows a familiar theme. “The main five long‑term spending pressures are health and aged care, the NDIS, defence, and interest payments on Government debt. Combined, these spending categories are projected to increase by 5.6 percentage points of GDP over the 40 years from 2022–23 to 2062–63.”

On the crucial issue of productivity, which has languished for years, the report downgrades the assumption for productivity growth “from its 30-year average of around 1.5% to the recent 20-year average of around 1.2%.

“Placing more weight on recent history better reflects headwinds to productivity growth, such as continued structural change towards service industries, the costs of climate change, and diminishing returns from past reforms. This downgrade is consistent with forecasts in other advanced economies.”

The report points to areas where there are opportunities to lift productivity growth.

These include reforms to reduce entry and exist barriers for firms, facilitating the diffusion of technology, and encouraging labour mobility. It also highlights the potential of digital innovations, including artificial intelligence.

On human capital, the report says, “The jobs of the future will require increasingly specialised skillsets and there is potential to support Australians at all stages of their human capital development. Promotion of foundational skills – such as in literacy and numeracy – at an early age will facilitate participation in the expanding knowledge economy over the next 40 years.”

Chalmers said the report “will make the critical point that the trajectory or productivity growth in the future is not a foregone conclusion, and it will depend on how we respond to the big shifts impacting our economy”.

Meanwhile the Business Council of Australia is unveiling a reform plan, titled Seize the Moment, for ways to reverse Australia’s “productivity slump” and boost competitiveness. It claims if implemented the reform package would “leave each Australian $7000 better off a year after a decade”.

Among its multiple proposals, the BCA says there should be “broad-based reform of the tax system to minimise distortions and increase incentives to invest, innovate and hire”.

It also says federal and state governments should commit to a “10-year national net zero roadmap based on a whole-of-system approach to decarbonising the economy to 2050”. It calls for more action to increase women’s economic participation, a more flexible industrial relations system, “a coherent system of lifelong learning”, and an agenda for microeconomic reform.![]()

Michelle Grattan is a professorial fellow at the University of Canberra.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Handpicked for you

Want to boost the economy? Link parental leave payments to prior earnings

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.