Australia is going through another supply chain crisis. Stocks of AdBlue, an exhaust fluid used in newer diesel cars and trucks to reduce pollution, are getting dangerously low.

The culprit is a shortage of synthesised urea, an ingredient which local AdBlue makers import mostly from Russia and China. It has uses from plywood to cosmetics and fertilisers. High demand, particularly from farmers, has led to a global supply shortage.

In July, Chinese urea makers began restricting exports in response to fluctuations in the local market. International prices soared 50% between September and October, but that was not enough to stabilise supply and demand.

For Australia the alarm bells rang loudly last week when the Australian Trucking Association warned AdBlue stocks would run out in February. Some are more pessimistic, saying supplies will be gone by Christmas.

What happens if Australia runs out of AdBlue

AdBlue helps newer-model diesel vehicles meet emissions standards by breaking down harmful nitrogen oxides. If you own a diesel car with an AdBlue tank, your car’s engine is programmed to not start once you run out of it.

The good news is that a typical car can travel more than 1000 km on 1 litre of AdBlue. Cars typically have tanks holding at least 10 litres. So one tank should keep you safe for at least six months.

For trucks it’s a different story. They typically clock up more kilometres on the road and are less efficient, using about 1 litre of AdBlue every 70 kilometres.

However, roughly half of Australia’s trucks don’t use AdBlue due to their age. The average age of Australia’s truck fleet is 15 years, compared with 13 years for Europe and less than 10 years for Germany. Also, emission regulation in Australia is less stringent than in the European Union.

In a worst-case scenario, where no solution is found and AdBlue supply stops, we may have to rely on these older trucks. Newer trucks could be remapped to run while polluting considerably more. But this is technically difficult, and will require temporary changes to Australian emission standards.

No one wants to go down that road. That’s why the federal government has established a taskforce to fix the problem.

How to solve the AdBlue supply crisis

Most supply chain crisis are based on hiccups in coordination.

Global AdBlue production, transportation and storage is under pressure but not disrupted. Federal energy minister Angus Taylor said last Thursday that Australia had enough AdBlue to last at least five weeks, and shipments en route would cover another two weeks. And more is yet to come.

Seven weeks will put us well into late January. By then we will be past Christmas, with less cargo and fewer parcels to move. This will bring relief to some logistic providers, who will be in a better position to stretch out their AdBlue stocks.

This should buy more time for the AdBlue taskforce to find solutions.

For example, it can recommend the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission suspend its usual anti-collusion rules that prevent competitors from talking to each other to cooperate. It did this in 2020 with the supermarkets, medical suppliers, banks and telecommunications companies to help them through the beginnings of the COVID-19 storm.

Another lesson to from past supply crises — particularly in supermarket supplies — is suppressing the chance of a self-creating crisis due to panic buying or stockpiling behaviour.

Limits on sales may be needed. If every transporter and diesel vehicle owner decides now is the time to fill their AdBlue tanks, stocks will deteriorate sooner.

The taskforce will be looking for suppliers less affected by the Chinese ban, and for ways to best distribute the stock we have. All these actions together should be enough to soon turn the corner on AdBlue shortages.

Is there a wider supply chain problem?

Whether this crisis points to a systemic problem that needs fixing depends on one’s perspective. It is a byproduct of globalisation, which expands supply chains but make them more vulnerable.

Economies of scale generally (but not always) make it more efficient and cheaper to have one big factory at one place than many small factories across the globe. The problem is when something happens to that one factory.

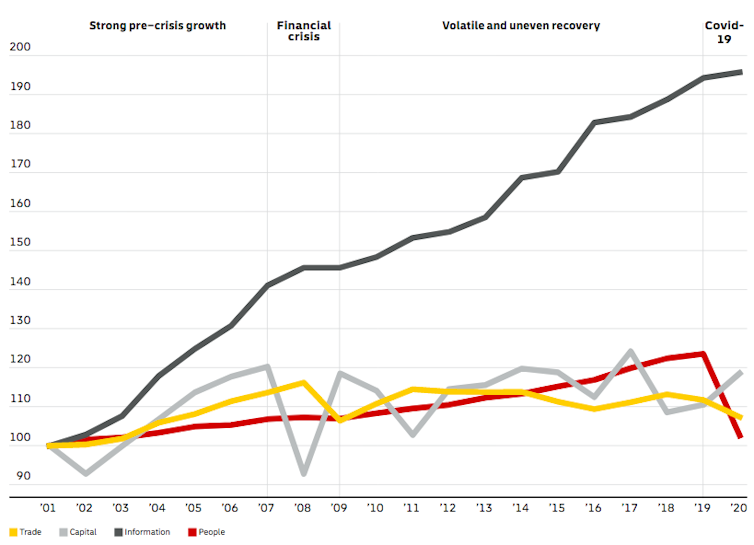

While there has been talk about a more strategic approach to “onshoring”, COVID-19 did not change the game much. The DHL Global Connectedness Index shows globalisation “has been much more resilient through the COVID-19 crisis than many predicted”.

Four pillars of global connectedness, 2001 – 2020

DHL Global Connectedness Index 2021 Update

A Productivity Commission report published in August was relatively relaxed about the risks to Australia. It highlighted that only a few critical products were vulnerable, though did note Australia’s over-reliance on much-needed chemicals coming from overseas (without mentioning urea or AdBlue specifically).

The call for more manufacturing in Australia faces the hard truth that once a crisis passes and cracks in supply chains mend, most of the time the local industry can’t compete with imports.

COVID-19 has, at least, pushed businesses to embrace a “China plus one” supply strategy. They have also increased inventories — moving from “just-in-time” to “just-in-case”.

So the two morals of this story, as with many others, is not put all your eggs in one basket, and put aside for a rainy day. AdBlue included!![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Handpicked for you

CSIRO: Every $1 invested in R&D creates $3.50 in benefits for Australia

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.